Angola

The territory that we call Angola nowadays is much larger than what was initially identified as Angola, or the colony of Angola, in the late sixteenth century. Several populations occupied the territory, with different levels of political organization. The arrival of Portuguese merchants in the late sixteenth century transformed the landscape, resulting in violent occupation of the territory, and the establishment of colonial settlements, including Luanda and Benguela. These two towns were not too different from other colonial spaces, such as Goa, Salvador, or Rio de Janeiro. There were fortresses and Catholic Churches, associated with Portuguese colonialism, while West Central Africans, speakers of Kimbundu and Umbundu languages, formed most of the population. These populations have been forced to relocate several times due to colonial presence and raids associated with the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade. For the purpose of the project “Land Dispossession, Inequality, and the Legacies of Slavery in Africa and Latin America,” we will focus on Benguela and land tenure struggles in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

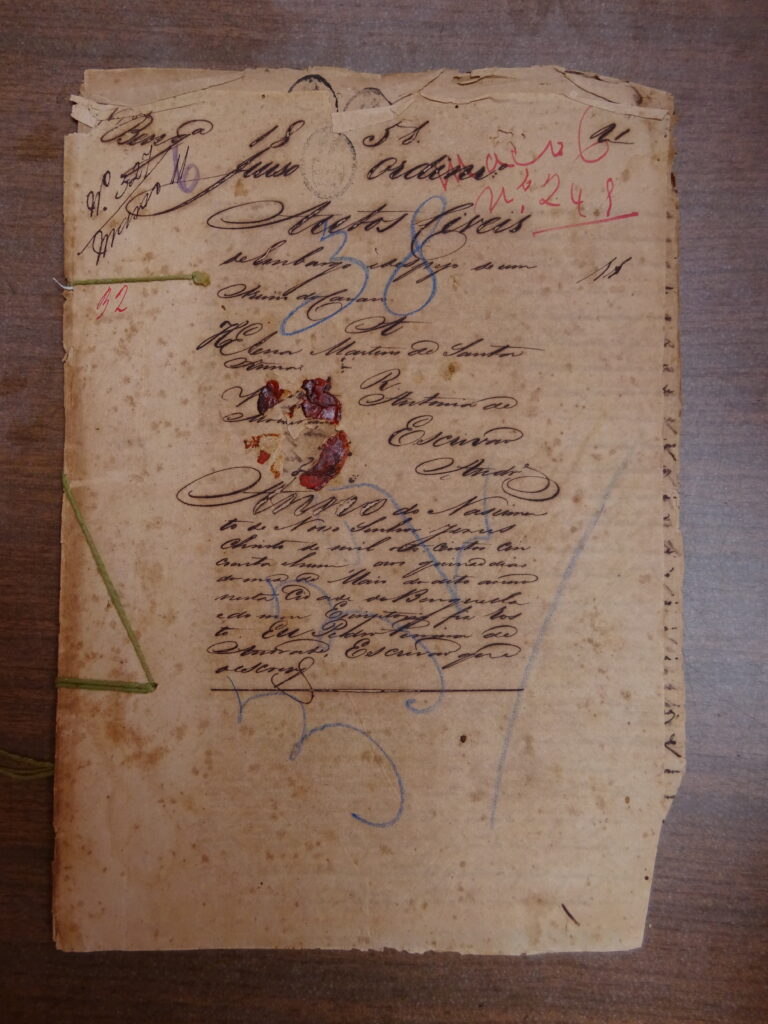

An aspect we will examine is how colonial courts created legal categories that dispossessed poor men and women from their lands. Colonial courts were fundamental in building up liberal property law and regimes of land tenure. In Angola, foreigner or colonial subjects could file “justification of possession” lawsuits. These lawsuits could result in the issuance of a property title if the plaintiff proved possession of a plot of land. This kind of lawsuit fell under the so-called “voluntary jurisdiction,” that is, they did not involve a conflict between parties, but a person who wanted the courts to declare his/her/their rights. Consequently, plaintiffs filed cases, and the court officers had no obligation to summoned anyone who could contest plaintiffs’ claim. Evidence of possession which plaintiffs put forward was that they had Black “servants” (serviçais) working on their land. Judges never summoned or heard any servants. Imbued with racialized conceptions about land use, plaintiffs and judges alike assumed that Black men and women working on the land were indeed servants, without ownership rights. They never raised the possibility that these so-called “servants” could hold land tenure rights, i.e. be the legitimate landowners. This section of the project analyzes court cases to understand how property titles consolidated the dispossession of West Central African.